Ethics and Religion

Ethics and Religion

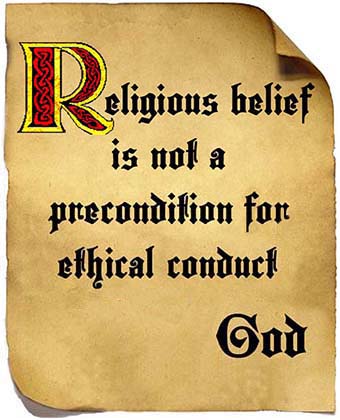

In a discussion about the origin of ethics it was suggested I “hated” religion ... well, certainly not. But - while I do not like the term ‘hate’ - I strongly oppose any reference to any wisdom that is based on revelation.

This is my stance on religion … there often is nothing wrong with social constructs based on religions (excepting the sort of religions that are the basis for ISIS etc.) but anything derived from revelation and the literal belief in God is alien to me ... so I go along with Douglas Adams, when he says "I am fascinated by religions, I'm just stumped people take them seriously."

Anyway, in that discussion the point was made that society's ethics derive from Christian values. I countered that ethical principles existed long before Christ (Confucius, Zoroaster, Lao Tsu et al) and since Christ outside of Christianity.

One over-arching point I would like to make about the strict belief in God and the notion that ethics derive from religious doctrines is that they may lead to war ... the Crusades, The Thirty Years War and the Islamic sectarian wars in the Middle East come to mind. If you get killed by a suicide bomber, it's because he got his ethical guidelines from the fundamentalist interpretation of Islam (which tell him he'll go to paradise through his deed).

In my book en.light.en.ment I have many essays that touch on this subject ... indeed, too many to list here; as a matter of fact, in a way I can say my book largely is about this subject matter. So, what follows is dear to me.

With content from Wikipedia, Wikipedia, The Conversation, the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Project Syndicate at Harvard Uni, American Atheists and the Guardian.

From the beginning of the Abrahamic faiths and of Greek philosophy, religion and morality have been closely intertwined. This is true whether we go back within Greek philosophy or within Christianity, Judaism and Islam … and there are others on Eastern thought like Ethics in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism and Chinese Ethics. It is clear that morality and religion have been inseparable until very recently (in fact until the Age of Enlightenment) and that our moral vocabulary is still deeply infused with this history.

Ethics Without Gods. One of the first questions Atheists are asked by true believers and doubters alike is, “If you don’t believe in God, there’s nothing to prevent you from committing crimes, is there? Without the fear of hell-fire and eternal damnation, you can do anything you like, can’t you?”

It is hard to believe that even intelligent and educated people could hold such an opinion, but they do! It seems never to have occurred to them that the Greeks and Romans, whose gods and goddesses were something less than paragons of virtue, nevertheless led lives not obviously worse than those of the Baptists of Alabama! Moreover, pagans such as Aristotle and Marcus Aurelius - although their systems are not suitable for us today - managed to produce ethical treatises of great sophistication, a sophistication rarely if ever equaled by Christian moralists.

The answer to the questions posed above is, of course, “Absolutely not!” The behavior of Atheists is subject to the same rules of sociology, psychology, and neurophysiology that govern the behavior of all members of our species, religionists included.

Moreover, despite protestations to the contrary, we may assert as a general rule that when religionists practice ethical behavior, it isn’t really due to their fear of hell-fire and damnation, nor is it due to their hopes of heaven. Ethical behavior - regardless of who the practitioner may be - results always from the same causes and is regulated by the same forces, and has nothing to do with the presence or absence of religious belief.

Does Ethics Require Religion? The relationship between religion and ethics is about the relationship between revelation and reason. Religion is based in some measure on the idea that God (or some deity) reveals insights about life and its true meaning. These insights are collected in texts (the Bible, the Torah, the Koran, etc.) and presented as 'revelation'.

Ethics, from a strictly humanistic perspective, is based on the tenets of reason: Anything that is not rationally verifiable cannot be considered justifiable. From this perspective, ethical principles need not derive their authority from religious doctrine. Instead, these principles are upheld for their value in promoting independent and responsible individuals - people who are capable of making decisions that maximize their own well-being while respecting the well-being of others.

Aristotle said that cultivating qualities (he called them 'virtues') like prudence, reason, accommodation, compromise, moderation, wisdom, honesty, and truthfulness, among others, would enable us all to enter the discussions and conflicts between religion and ethics - where differences exist - with a measure of moderation and agreement. When ethics and religion collide, nobody wins; when religion and ethics find room for robust discussion and agreement, we maximize the prospects for constructive choices in our society.

The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso: “All the world's major religions, with their emphasis on love, compassion, patience, tolerance, and forgiveness can and do promote inner values. But the reality of the world today is that grounding ethics in religion is no longer adequate. This is why I am increasingly convinced that the time has come to find a way of thinking about spirituality and ethics beyond religion altogether.”

Is religion necessary for morality? Many people think it is outrageous, or even blasphemous, to deny that morality is of divine origin. Either some divine being crafted our moral sense during the period of creation or we picked it up from the teachings of organized religion. Both views see the same endpoint: we need religion to curb nature’s vices.

In the United States, where the conservative right argues that we should turn to religion for moral insights and inspiration, the gap between government and religion is rapidly diminishing. Abortion and the withdrawal of life-support are increasingly being challenged by the view that these acts are strictly against God’s word “thou shalt not kill” (note: originally translated as "murder"). And religion has once again begun to make its way back into public schools, seeking equal status alongside a scientific theory of human nature.

Yet problems abound for the view that morality comes from God. One problem is that we cannot, without lapsing into tautology, simultaneously say that God is good, and that he gave us our sense of good and bad. For then we are simply saying that God is in accordance with God’s standards. That lacks the resonance of "Praise the Lord!" or "Allah is great!"

A second problem is that there are no moral principles shared by all religious people (disregarding their specific religious membership). Atheists and agnostics do not behave less morally than religious believers, even if their virtuous acts are mediated by different principles. They often have as strong and sound a sense of right and wrong as anyone, including involvement in movements to abolish slavery and contribute to relief efforts associated with human suffering.

The third difficulty for the view that morality has its origin in religion is that despite the sharp doctrinal differences between the world’s major religions, and for that matter cultures like ancient China in which religion has been less significant than philosophical outlooks like Confucianism, some elements of morality seem to be universal. One view is that a divine creator handed us the universal bits at the moment of creation.

The alternative, consistent with the facts of biology and geology, is that we have evolved, over millions of years, a moral faculty that generates intuitions about right and wrong. For the first time, research in the cognitive sciences, building on theoretical arguments emerging from moral philosophy, has made it possible to resolve the ancient dispute about the origin and nature of morality.

The converse is also true: religion has led people to commit a long litany of horrendous crimes, from God’s command to Moses to slaughter the Midianites, men, women, boys and non-virginal girls, through the Crusades, the Inquisition, the Thirty Years War, innumerable conflicts between Sunni and Shiite Moslems, and terrorists who blow themselves up in the confident belief that they are going straight to paradise.

Secular morality ... is the aspect of philosophy that deals with morality outside of religious traditions. Modern examples include humanism and freethinking. Additional philosophies with ancient roots include those such as skepticism and virtue ethics.

Secular ethics ... is a branch of moral philosophy in which ethics is based solely on human faculties such as logic, empathy, reason or moral intuition, and not derived from supernatural revelation or guidance - the source of ethics in many religions. Secular ethics refers to any ethical system that does not draw on the supernatural, and includes humanism, secularism and freethinking.

A classical example of literature on secular ethics is the Kural text, authored by the ancient Tamil Indian philosopher Valluvar who lived during the 1st century BCE. Considered one of the greatest works ever written on chiefly secular ethics and morality, it is known for its universality and non-denominational nature.

Furthermore, much of ancient Far Eastern thought is deeply concerned with human goodness without placing much if any stock in the importance of gods or spirits. Other philosophers have proposed various ideas about how to determine right and wrong actions. An example is Immanuel Kant's categorical imperative.

Some believe that religions provide poor guides to moral behavior. Various commentators, such as Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion), Sam Harris

(The End of Faith) and Christopher Hitchens (God Is Not Great) are among those who have asserted this view.

Freethought ... is a philosophical viewpoint that holds that opinions should be formed on the basis of science, logic, and reason, and should not be influenced by authority, tradition, or other dogmas. Freethinkers strive to build their opinions on the basis of facts, scientific inquiry, and logical principles, independent of any logical fallacies or intellectually limiting effects of authority, confirmation bias, cognitive bias, conventional wisdom, popular culture, prejudice, sectarianism, tradition, urban legend, and all other dogmas.

Secular humanism ... focuses on the way human beings can lead happy and functional lives. It posits that human beings are capable of being ethical and moral without religion or God, it neither assumes humans to be inherently evil or innately good, nor presents humans as "above nature" or superior to it. Rather, the humanist life stance emphasizes the unique responsibility facing humanity and the ethical consequences of human decisions.

Fundamental to the concept of secular humanism is the strongly held viewpoint that ideology - be it religious or political - must be thoroughly examined by each individual and not simply accepted or rejected on faith. Along with this, an essential part of secular humanism is a continually adapting search for truth, primarily through science and philosophy.

Religion and morality are not synonymous. Morality does not necessarily depend upon religion, though for some, this is an almost automatic assumption. According to The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics, religion and morality "are to be defined differently and have no definitional connections with each other. Conceptually and in principle, morality and a religious value system are two distinct kinds of value systems or action guides."

Richard Holloway proposes Godless Morality in his book Keep Religion Out of Ethics and posits: If God is the author of our moral code, how can we challenge it? Has increasing secularism eroded traditional moral systems? Bishop Richard Holloway challenges our assumptions and offers provocative solutions to these questions. He argues that moral codes are human constructs. (Goodreads)

Religious commentators have asserted that a moral life cannot be led without an absolute lawgiver as a guide. Other observers assert that moral behavior does not rely on religious tenets, and secular commentators point to ethical challenges within various religions that conflict with contemporary social norms.

Indeed, Bertrand Russell said: "There are also, in most religions, specific ethical tenets which do definite harm. The Catholic condemnation of birth control, if it could prevail, would make the mitigation of poverty and the abolition of war impossible. The Hindu beliefs that the cow is a sacred animal and that it is wicked for widows to remarry cause quite needless suffering.”

According to Bertrand Russell, "Clergymen almost necessarily fail in two ways as teachers of morals. They condemn acts which do no harm and they condone acts which do great harm." He cites an example of a clergyman who was warned by a physician that his wife would die if she had another (her tenth) child, but impregnated her regardless, which resulted in her death. "No one condemned him; he retained his benefice and married again. So long as clergymen continue to condone cruelty and condemn 'innocent' pleasure, they can only do harm as guardians of the morals of the young."

"You find this curious fact, that the more intense has been the religion of any period and the more profound has been the dogmatic belief, the greater has been the cruelty and the worse has been the state of affairs ... You find as you look around the world that every single bit of progress in humane feeling, every improvement in the criminal law, every step toward the diminution of war, every step toward better treatment of the colored races, or every mitigation of slavery, every moral progress that there has been in the world, has been consistently opposed by the organized churches of the world."

Russell further states that, "the sense of sin which dominates many children and young people and often lasts on into later life is a misery and a source of distortion that serves no useful purpose of any sort or kind."

Russel allows that religious sentiments have, historically, sometimes led to morally acceptable behavior, but asserts that, "in the present day (1954), such good as might be done by imputing a theological origin to morals is inextricably bound up with such grave evils that the good becomes insignificant in comparison."

Philosopher David Hume stated that, "the greatest crimes have been found, in many instances, to be compatible with a superstitious piety and devotion; hence it is justly regarded as unsafe to draw any inference in favor of a man's morals, from the fervor or strictness of his religious exercises, even though he himself believe them sincere."

The proper role of ethical reasoning is to highlight acts of two kinds: those which enhance the well-being of others - that warrant our praise - and those that harm or diminish the well-being of others - and thus warrant our criticism.

But problems that could arise if religions defined ethics, such as:

1. religious practices like "torturing unbelievers or burning them alive" potentially being labeled "ethical"

2. the lack of a common religious baseline across humanity because religions provide different theological definitions for the idea of sin

Furthermore, various documents, such as the UN Declaration of Human Rights lay out "transcultural" and "trans-religious" ethical concepts and principles - such as slavery, genocide, torture, sexism, racism, murder, assault, fraud, deceit, and intimidation - which require no reliance on religion (or social convention) for us to understand they are "ethically wrong".

Religious values can diverge from commonly-held contemporary moral positions, such as those on murder, mass atrocities, and slavery. For example, Simon Blackburn states that "apologists for Hinduism defend or explain away its involvement with the caste system, and apologists for Islam defend or explain away its harsh penal code or its attitude to women and infidels".

In regard to Christianity, he states that the "Bible can be read as giving us a carte blanche for harsh attitudes to children, the mentally handicapped, animals, the environment, the divorced, unbelievers, people with various sexual habits, and elderly women".

He provides examples such as the phrase in Exodus 22:18 that has "helped to burn alive tens or hundreds of thousands of women in Europe and America": "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live," and notes that the Old Testament God apparently has "no problems with a slave-owning society", considers birth control a crime punishable by death, and "is keen on child abuse".