|

"I can't breathe."

__________________

Black Australia by the Numbers

The Conversation

see also my essays ABORIGINAL and BLACK

99

The number of deaths in custody documented by the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

432

The number of Indigenous Australians who have died in custody since (according to Guardian Australia’s Deaths Inside project).

2,481

The number of First Nations adults in prison for every 100,000 people.

164

The number of non-indigenous adults in prison for every 100,000 people.

2%

The percentage of Australia's adult population who are First Nations Australians.

28%

The percentage of Australia's prison population who are First Nations Australians

2015

The year David Dungay Jr was killed when prison officers restrained him, including with handcuffs, and pushed him face down on his bed and on the floor. One officer pushed a knee into his back. All along, Dungay was screaming that he could not breathe and could be heard gasping for air. An officer said ... "if you can scream, you can breathe".

Zero

The number of successful homicide prosecutions of a death in custody in Australia's criminal courts.

The Full Story about David Dungay

The death of David Dungay Jnr

The Guardian

One of the names chanted in the Australian protests sparked by the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis has been David Dungay. The eerie similarities between his case and the death of Floyd have brought his death in 2015 back into the spotlight. Both men were held down before they died, both cried ‘I can’t breathe’. Miles Herbert looks back at the death of David Dungay Jnr

_______________________________

Targeting police will do little to stop Aboriginal deaths in custody

By Don Weatherburn, SMH

Aboriginal people are too often the victims of racist and brutal policing. And yes, the way police treat Aboriginal children (and adults) needs to change. But the complete elimination of racist policing would do little to reduce the number of Aboriginal Australians in prison custody and the number who die there.

Police treatment of Aboriginal people and Aboriginal over-representation in prison are two distinct issues requiring different responses. The former requires change in the behaviour of police. The latter requires an Aboriginal-led government-supported effort to improve Indigenous outcomes in child welfare, health, education and employment.

Sixty-three per cent of Aboriginal people in prison are there for violent offences. The primary victims of this violence are Aboriginal women and children. The violence is a product of a chain of events that starts with colonisation and dispossession and stretches forward in time through trauma, loss of purpose, child neglect, substance abuse, depression, poor school performance and unemployment.

There should be no surprise in this. You can’t invade a country, drive the original inhabitants off their land, destroy their way of life, pass on your diseases, herd them into camps or on to islands, forcibly remove their children and expect this to have no long-term adverse effects.

Research at Harvard University has shown that the practice of slavery has done long-term damage to the economies of African countries from which slaves were taken. Similar research by Pauline Grosjean at the University of NSW has shown evidence of a link between clan violence in the Scottish highlands and violence in those parts of the southern United States to which many Scots emigrated.

The fact the high rate of Aboriginal involvement in serious crime has its origins in the sequelae of colonisation and dispossession does not mean there is nothing we can do to reduce the rate of Aboriginal imprisonment or the number of Aboriginal people dying in custody.

Aboriginal people know all too well what is happening in their communities. They’re painfully aware many of their children are sliding off the rails and into drug use, crime and despair. They want it to stop. They want our support and assistance in stopping it.

But it isn’t going to stop if we do nothing more than reform the law and change police procedures.

Real progress in reducing Aboriginal over-representation in custody will come only when we strengthen the hand of Aboriginal people who want to see their infants thrive, their children do well at school and those children get jobs when it is time to leave.

Don Weatherburn is a professor at the UNSW National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre and a former director of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

_______________________________

When I look at America torn apart,

I see my own family and Australia's history of racism

by Stan Grant, SMH

Stan Grant is a Wiradjuri man, journalist, ABC’s

Australian Indigenous and international affairs analyst

These are hard times. Times when it feels like we are forced to choose sides. Times when race matters and I wish it didn’t.

I wish we could stand for justice above race. But justice can’t be colour-blind, because injustice was never colour-blind.

When I look at America torn apart after the death of another black man killed at the hands of police, I see people who look like the people in my family. I see people with a history of racism that I share.

I am a world away, but bonded in struggle.

As a boy, raised in an Aboriginal family, in politics and the church I looked to the giants of America’s civil rights struggle: black pastors such as Ralph Abernathy, Jesse Jackson and of course Martin Luther King Jnr, men who believed that character should matter more than colour.

But for black people, has America ever truly been the land of the free?

This week I have thought of the words of the African-American writer Ta-Nehisi Coates: “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body – it is heritage.”

Coates wrote his seminal book Between the World and Me after one of his friends was shot dead by a policeman. In an open letter Coates warns his young son that “the police departments of your country have been endowed with the authority to destroy your body".

Sometimes Coates’ words seem too bleak, yet this week his words sound like prophesy to black Americans. This week, George Floyd is every black person in America who has died under a whip, lynched from a tree, or perished in a building set on fire by racists in white hoods.

This week Americans hear the great James Baldwin: “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.”

I have felt that rage here.

I felt it when I saw the boys of Don Dale bound and hooded and beaten and tear-gassed.

I feel that rage when I recall the stories of my own family’s past: of segregation, discrimination and police beatings.

I feel that rage when I think of how Indigenous people are the most incarcerated in our country. And how they die still in police cells: 432 black deaths in custody since the royal commission 29 years ago.

We should all be angry because when our country fails its people we all fail.

Yes, Australia has been good for me but too many of our people cannot say the same. Too many are lost to early graves, locked in endless cycles of poverty and misery.

This is the torment of our powerlessness; we know it is broken and still we fail to fix it.

This is the legacy of our history: those wounds of the soul that don’t heal and can so easily turn toxic.

History hangs so heavy in our world – on the streets of America, across the Middle East. It hangs heavy in the borderlands of Europe and behind the wall of China.

These are treacherous fault lines. From the grievance of history we construct our identity and identity at its worst can be a terrible thing. Identity can pit us against each other; we form our tribes and we tear each other apart.

The Indian philosopher and economist Amartya Sen was right: “identity can kill – and kill with abandon”.

How I wish we did not have to choose sides. How I wish we could slip the yoke of history. How I wish this was not about race.

But this week, it is hard to not see race when race is all we see. When people who have been branded by race seek the solidarity of race.

Dr King’s dream seems so far away.

Yet the violence can blind us to those people black and white marching together peacefully, those who still cling to what the greatest American president, Abraham Lincoln, called the better angels of our nature.

Democracy should be big enough to hold us all: regardless of colour or creed. And that’s the struggle of our age when around the world democracy is in retreat and authoritarianism is on the march.

That great beacon of liberty, that nation that promised to take in the poor and sick and huddled masses, the America of dreams, is ablaze, unable to police itself let alone the world.

It is sad to see and we are all poorer for it.

As we look to America, as people here march in solidarity with the best of America, we can save ourselves from the worst of America.

This is a moment to ask if our country can fulfil its promise. Can our great country be great for all? These are just words. Actions are so much harder and, judged by our actions, history tells us we have failed.

But history need not define us. We are not America; our streets thankfully are not battlegrounds. Here, the cry of justice need not be an invitation to hate.

_______________________________

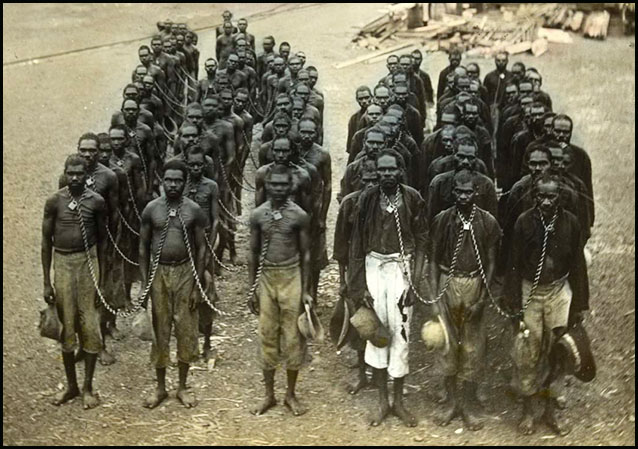

A photo titled: "Group of prisoners in neck chains, Wyndham, Western Australia",

dated between 1898 and 1906.CREDIT: STATE LIBRARY OF VICTORIA

'It's just denial': Bruce Pascoe, Labor

condemn PM's 'no slavery in Australia' claim, SMH

Author and historian Bruce Pascoe says Prime Minister Scott Morrison's claim there was no slavery in Australia is wrong, while Labor's Indigenous Australians spokeswoman has called for more truth-telling in the country's history.

_______________________________

Premier needs to act on model to save black lives

Teela Reid, SMH

The Black Lives Matter protests demonstrate precisely how the power of the people can force the government to confront the reality of Aboriginal deaths in custody and Indigenous incarceration on Australian soil.

The federal government reportedly intends to get tougher on state and territory governments when it comes to rates of Indigenous incarceration at its upcoming Close the Gap "refresh" negotiations next month.

A draft agreement to reduce the rate of Indigenous young people in custody by 19 per cent as of 2028 is apparently to be junked. A higher target will be set in response to the well-attended Black Lives Matter protests around Australia over the weekend.

What we know is that Close the Gap targets alone will not reduce the rapid incarceration of Indigenous Australians that has grown nationally from 19 per cent in 2000 to about 30 per cent in 2020. We need systemic change to eliminate institutional racism within the courts.

In NSW, Indigenous people are 2.8 per cent of the total population and represent approximately 25 per cent of the prison population. The statistics are shameful, but there is an opportunity to rewrite this narrative by transforming the criminal justice process of this state. Establishing the Walama Court is the key.

The Walama Court is designed to divert Aboriginal people away from the criminal justice process and reduce police contact by involving Aboriginal elders in the decision-making process within the District Court of NSW. And unlike the Children's Koori Court and other programs designed to reduce the number of Indigenous people in custody, it would be enshrined in legislation, with the guarantee of redistributing resources into the Aboriginal communities, not the police. We know a proper focus on rehabilitation, rather than punitive punishment like prisons, works.

A fundamental element underpinning the Walama Court is the importance of threading Aboriginal lore and cultural knowledge into the court process in the administration of justice. This is crucial given many judges hearing the stories of Aboriginal lives for the first time in court do not fully understand the intergenerational trauma the current system perpetrates.

Since 2015, I’ve been an active member of the Walama Working Group as a researcher and defence lawyer. The group is chaired by Judge Dina Yehia SC of the District Court. Her honour was a solicitor in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody representing Aboriginal families.

Aboriginal community members from across the nations of the Sydney region were involved in the development of the model as well as key stakeholders such as the NSW Public Defenders, the NSW Aboriginal Lands Council, the Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT, Legal Aid NSW, NSW Director of Public Prosecutions, NSW Community Corrections and the NSW Department of Justice. The model also has the endorsement of the NSW Barristers Association and the Law Council of Australia.

The word "Walama" means to "come back" or "to return" in Dharug language and it is precisely the objective of the court to ensure Aboriginal people return to the safety of their communities, come back to country and reconnect with their cultural identity, rather than languish inside a prison cell.

In 2018, the Walama Working Group officially presented the business case for the Walama Court to the NSW government directly to the office of the NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman. We understand Premier Gladys Berejikilian is aware of the proposal, although the State Parliament is yet to act on its implementation by passing the legislation required for its establishment.

The business case is legally and fiscally sound. It refers to an independent report produced by Price Waterhouse Cooper in 2017, Indigenous Incarceration: Unlock the Facts. The PwC report predicted: "If nothing is done to address disproportionately high rates of Indigenous incarceration, this cost will rise to $9.7 billion per year in 2020 and $19.8 billion per year in 2040. Closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous rates of incarceration would generate savings to the Australian economy of $18.9 billion per year in 2040." The overall justice system cost for NSW in 2016 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ incarceration was $870 million.

Ultimately, the Walama Court will reduce Indigenous incarceration as well as reduce costs. The Australian Law Reform Commission Report, Pathways to Justice – Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People (2017), specifically identified the Walama Court proposal when making recommendation for specialist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ sentencing courts by state and territory governments.

It highlighted the Walama Court as a prime example of how to incorporate individualised case management and wraparound services in a culturally safe way through systemic change to revolutionise the court process. The NSW Ice Inquiry report (2020) also recommended the NSW government implement the Walama Court.

If Black Lives Matter in NSW, now is the time for the state to establish the Walama Court. It should do so immediately. The hard work in design of the model has been done, the business case is with the NSW government, let’s not let it gather dust.

Teela Reid is a lawyer and Wiradjuri/Wailwan woman.

_______________________________

From Seth Godin's blog:

Black Lives Matter.

The systemic, cruel and depersonalizing history of Black subjugation in my county has and continues to be a crime against humanity. It’s based on a desire to maintain power and false assumptions about how the world works and how it can work. It’s been amplified by systems that were often put in place with mal-intent, or sometimes simply because they felt expedient. It’s painful to look at and far more painful to be part of or to admit that exists in the things that we build.

We can’t permit the murder of people because of the color of their skin. Institutional racism is real, it’s often invisible, and it’s pernicious.

And White Supremacy is a loaded term precisely because the systems and their terrible effects are very real, widespread and run deep.

The benefit of the doubt is powerful indeed, and that benefit has helped me and people like me for generations. I’m ashamed of how we got here, and want to more powerfully contribute and model how we can get better, together.

It doesn’t matter how many blog posts about justice I write, or how clear I try to be about the power of diversity in our organizations. Not if I’m leaving doubt about the scale and enormity of the suffering that people feel, not just them-selves, but for their parents before them and for the kids that will follow them.

It’s easier to look away and to decide that this is a problem for someone else. It’s actually a problem for all of us. And problems have solutions and problems are uncomfortable.

|